Listening to the sounds his feet are making (“Crush, crack, crick, crick”), the poet in Stephen recalls a familiar fragment of verse and thinks, “Rhythm begins, you see. I hear. A catalectic tetrameter of iambs marching.” Tetrameter is a metrical verse line containing four feet such as iambs (dee DUM), and catalectic, from a Greek word meaning “incomplete” or “left off,” refers to the omission of a syllable from the final foot. But in the tetrameter line that Stephen recites (the second one is trimeter), either the opening syllable is missing or the meter is trochaic (DUM dee). Additional confusion is introduced in the Gabler edition by changing “A catalectic” to “Acatalectic,” meaning “without incompletion”––i.e., complete.

Read Lessexpand_less

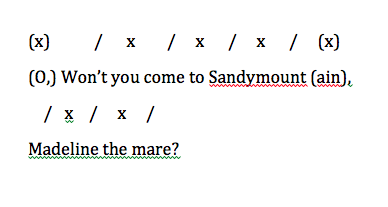

Scanned as iambic tetrameter, “Won’t you come to Sandymount” is missing a syllable from the beginning––as if chopped down from “O, won’t you come to Sandymount.” The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics observes that “The term ‘initial truncation’ is used to describe the omission of the first syllable of a (generally iambic) line. A line so truncated is also called a ‘headless’ (acephalous) line.” Stephen appears to be thinking of this kind of truncation, because when he continues to brood on the fragment of verse he hews a syllable off the beginning of the next line, changing “Madeline the mare” to “deline the mare.”

The result is two iambs, but with the missing syllable restored this line sounds trochaic. If that is the case, then what’s missing is an unstressed syllable after “mare.” The encyclopedia observes that “Truncation is frequent in trochaic verse, where the line of complete trochaic feet tends to create an effect of monotony.” (The same is true of dactylic verse in English.) If both lines are catalectic, Stephen is wrong about “iambs marching.” If the first line is iambic, he is wrong about “catalectic.”

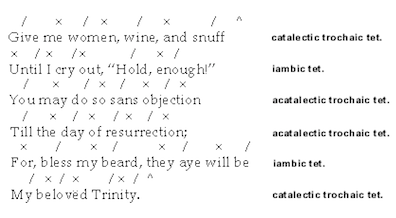

The two metrical rhythms flip over into one another easily, so iambic and trochaic lines can readily be mixed, as in the Keats poem shown here. Its first and last lines are catalectic trochaic tetrameter, with the missing final syllable marked by a caret. The second and fifth lines are regular, or “acatalectic,” iambic tetrameter. The third and fourth lines are regular trochaic tetrameter. One could argue that the second line gives evidence for scanning Stephen’s first line iambically: if initially truncated to read “Till I cry out, ‘Hold, enough!’,” it becomes rhythmically identical to “Won’t you come to Sandymount.” But the same is true of the trochaic line “Give me women, wine, and snuff.” On balance, it seems that Stephen should be thinking of a catalectic tetrameter of trochees marching.

Whichever way the line is scanned, in no rational universe could it ever be described as acatalectic––i.e., metrically regular. The Gabler text of Ulysses does just that, egregiously emending the two-word phrase to “Acatalectic.” All print editions from 1922 onward have “A catalectic,” and the version that Joyce published in The Little Review in 1918 reads “Catalectic tetrameter of iambs marching.” Gabler often seems to regard the Rosenbach manuscript as an authoritative arbiter of disputes, and Joyce’s handwriting there does appears to read “Acatalectic.” But plucking a word that makes no sense from this document to replace a phrase that does make sense, and that has been repeatedly scrutinized and affirmed over the course of a long publishing history, constitutes editorial malpractice.

In his revised collection of annotations, Slote offers a lengthy explanation of Gabler’s choice by observing that Joyce himself wavered between the two variants. He wrote “Acatalectic” in “several drafts” but changed it to “A catalectic” on a galley proof, and then on the same proof page went back to the one-word form. The two-word form appeared on a later proof and thus entered the first edition, but the confusion continued as Joyce compiled lists of errata. “Gabler reverts to the one-word form,” Slote observes, “because that was the last version attested in Joyce’s hand,” but, “in an unpublished letter to Harriet Shaw Weaver, from 3 November 1922, Joyce relented and endorsed the two-word form.”

This interesting history provides context for Gabler’s decision but does not excuse it: an author’s errors cannot absolve the editor of his own sins. Joyce apparently made a mistake in moments of uncertainty and thought better of it when publication was imminent. (He knew no classical Greek and probably had nothing like The Princeton Encyclopedia on his shelves.) Replacing the more or less right word of other printed texts with a totally wrong one adds editorial caprice to authorial confusion.

Scanning of the lines with “/” for stressed syllables and “x” for unstressed, and two added syllables that could make the first line either catalectic iambic tetrameter or catalectic trochaic tetrameter

Timothy Steele’s scansion of a poem by John Keats, using the same marks for stressed and unstressed syllables and carets for syllables omitted in catalectic lines.

What do you think?

Show comments / Leave a comment